Decoding: My Art, Sexuality and Disability

1/2

For roughly 300 days, I was stuck indoors during the lockdown in 2020. Away from obligations and diversions, I had no choice but to be with my thoughts. Spending so much time with myself forced me to feel the need to communicate with my body, and it turned out that it had a lot to say.

As an artist, I recorded these conversations through a series of self-portraits.

2/2

Four years later, my recent musings on disabilities made me reflect on my own disabled past, eventually leading me to these self-portraits. This document is a set of journal entries that attempt to simultaneously decode my art and the point where my queerness meets my disability.

Caution: This content contains nudity, expressions of anger, and unfiltered emotions.

Shame and Nudity

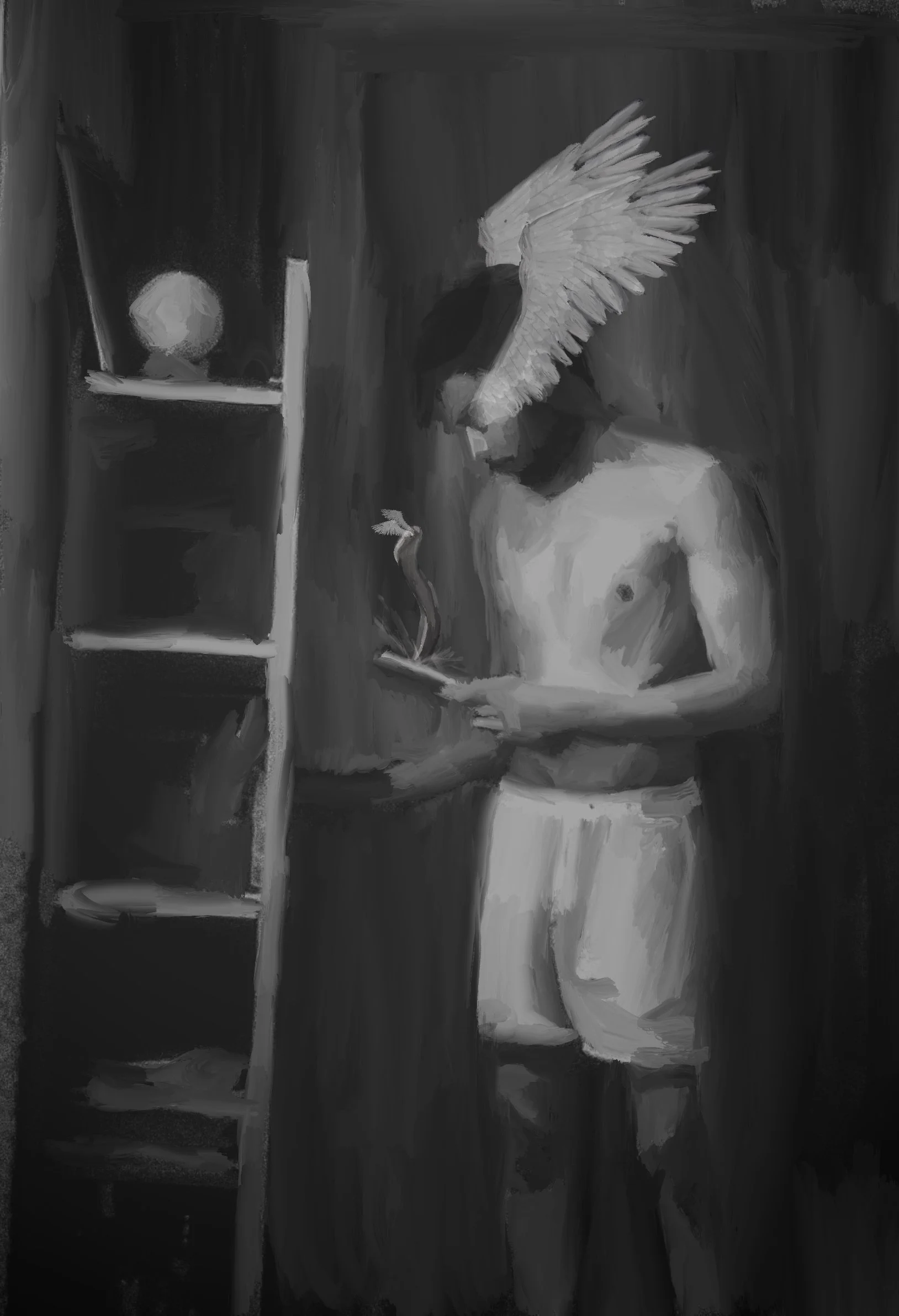

As a self-portrait artist, most of my artwork involves nudity. This process has given me the power to depict my own reality in the most authentic way — a right that I fought to get.

As a queer individual with invisible disabilities, I have been shamed both for my body and my mind. I have been made to feel not only unworthy but also undesirable. Concealing my true self became a survival strategy, which is why embracing nudity now empowers me.

Shaming operates as a mechanism of control. It not only deprives you of your inherent belongings but also coerces you into adopting another person’s version of reality. This occurs because your self-worth diminishes to such an extent that you find it difficult to trust your own thoughts and perspectives.

In the past, I almost had become comfortable with the fact that I can only feel joy through other people’s experience of it, for its true existence for me was always about the lack of it.

However, with what I can only call luck, I found my way out, and by the time I was 29 years old, I had come out as queer, non-binary, disabled, shameless, unapologetic, and very tired. But throughout this journey, one thing remained with me, and that was my art.

Art allowed me to feel joy without shame, and love or hate myself but on my own terms. Art helped me believe that I, too, a queer disabled person, deserve joy.

Shaming, an act of violence, forcibly robbed me of joy. Yet, for the longest time, I failed to recognize shaming for the harm it inflicted. It was wielded as a weapon to deconstruct every facet of my identity that challenged conventional norms — the very aspects that were authentic but unsettling to those who conform.

I faced shame for my misspelled words, was branded as weak for voicing discomfort with intense lights and loud noises, and was labeled as cranky for expressing confusion and fear in response to a world that seemed overwhelming and perplexing.

But soon, I realized that the core issue wasn’t rooted in my differences from the rest but rather in my authenticity, a rare thing in this conforming world. Shame was used to pressure me into conformity, and when my disability or queerness made such conformity impossible, the alternative was expecting me to hide — retreating until I faded from their memory and until I was invisible to them so they wouldn’t feel bad about themselves because I reminded them of courage that they don’t have.

That’s precisely why my art, much like most art, serves as a mode of protest. The portrayal of nudity becomes a declaration that proclaims my complete self’s presence — queerness and disability in all its unfiltered splendor, embracing the hair and lines, the brown skin, the absence of their understanding of masculinity, and a distinct mind that is so different that they call its existence a “condition.”

My art is a way to stand on the top and say, look at my cute butt — it’s here to stay, and shame doesn’t work on me anymore.

Invisibility of My Invisible Disability

Envision moving with two unyielding weights fastened to your waist, an enduring burden every day. No matter where your journey takes you, these weights persistently accompany you. Over time, as you grow, you become accustomed to their constant presence to the point where you nearly forget they’re there. Yet, you’re abruptly reminded of them when you’re required to ascend ten flights of stairs in emulation of others or when you must run three miles to match someone else’s pace.

Now, picture being unable to see or touch these stones but always knowing that the weight exists — and its inconvenience when you have to do simple tasks in life. This is what my invisible disability feels like.

The primary challenge stemming from my disability wasn’t merely the inability to convey it to others; it was the struggle to comprehend it myself. Even with the diagnosis of dyslexia and ADHD, I’m aware that these conditions alone can’t fully account for the daily encounters I undergo. There exists an additional layer — a layer I don’t understand.

This need for persistent preoccupation with confusion is also (ironically) a byproduct of how my brain authentically operates.

Both my queerness and disability, two substantial facets of my life, have remained concealed from sight yet palpably present in their own way. Their existence manifests within my art as accompanying elements to the central figure — my own body portrayed in my paintings.

In many of my self-portraits, various objects such as clouds, plants, or nuanced lighting are strategically integrated, prompting me to delve further into the art. That there is more than what you see, or perhaps what you see, is “strange” but is a part of me.

However, the incorporation of these objects only began to surface after art became a tool for unraveling my queerness, which in turn facilitated the exploration of my disability. I came to understand that the colors I had been experimenting with held insights into the depths of my various identities. The realization dawned that life isn’t limited to a singular shade; there exists a spectrum. Even solid pink, lavender, and yellow possess a multitude of variations. Furthermore, the ability to blend colors to generate new hues became a metaphor for my evolving sense of self.

Despite attaining this deep self-awareness, a process that required years of introspection, my struggles remain invisible. Perhaps this very mystery is its very essence. What has provided solace amid this confusion is my art and my queerness, allowing me to find comfort in this intricate reality.

These facets have empowered me to transcend the notion that I require society’s endorsed definitions. I can reject diagnoses that fail to grasp my essence. Armed with the knowledge cultivated by my art and queerness, I’ve discovered that this understanding is sufficient for me to exist, flourish, and even confront mortality happily when the time comes.

While my queerness helped my disability, embracing my disability also illuminated my perception of queerness as a remarkable gift.

Creating My Own Reality

As an artist, my obsession lies in the act of creation. There’s nothing that fills me with as much delight as composing something entirely new from nothing. For me, creation transcends mere making; it’s a profound mode of expression. It’s about envisioning the existence of elements yet unseen, and if no one has brought them to life, I take it upon myself to give birth to them.

As a queer-disabled body, it was very early on in my life that it was evident that the world isn’t made for me and it is incapable of creating a space for my fantasies, my desires, and my pleasures — so I started creating my own world.

I carefully started crafting the pieces that I wanted and discarding those that gave me no joy. I stepped into realms that allowed exploration and intertwined my essence with spaces that whispered possibility. Along this journey, I encountered kindred souls whose hearts beat in sync with life in its most giving form, where existence itself mirrored the euphoria of intoxication.

Amid the imprints of systematic marginalization that have engraved scars meant to linger even beyond lifetimes, there emerge days when I extend gratitude to the stars above. Gratitude for weaving the threads of my existence differently, for denying me the cloak of privilege, and in turn, gifting me with the deep ability to cherish life in a manner that eludes the grasp of those stuck in privilege.

This sentiment is a difficult one to transcribe onto paper, yet it’s a sentiment that demands acknowledgment. I can hardly fathom living in another’s skin, donning shoes that fail to fit, draping myself in hues that lack vibrancy, while rigorously policing my own essence. Perhaps I could perish one day due to the way I choose to navigate existence.

The notion looms that I might face bullets while relishing moments within a pulsing club. But there are instances when I contemplate if such a fate could hold a form of value. Could it be that it’s worth more than enduring a repetitive cycle of daily deaths, all endured within the span of a single life until the final breath draws near? I don’t know.

The interplay between imagination and reality, a manifestation born from a denied existence as a queer-disabled individual, frequently finds its expression within my art as surreal elements. Even though my art exists on canvas, the experience of it exists with me in reality.

Marginalization has led me to believe that I don’t belong to this world — and it’s true, I don’t. So I created my own, as did many others — a world that is far more beautiful and invites everyone who wants to experience true joy, happiness, and everything alluring that life has to offer.

My art acts like a portal to that world, and it pushes me to extend it so others stuck in the “real world” can find a way to realize what life truly can be if we let go of what we have constructed and embrace what exists without it.